“…And there are those jobs that are not only boring and unpleasant, but would make little difference to our existence if they were not there, except that someone is earning a living from them…”

Again and again we read it in the papers and hear it on the news; politicians, economists and journalists telling us about the vital need for jobs. This preoccupation with the creation of jobs as a solution to the unemployment problem is at the top of the agenda for pretty much all sides of politics and economic thought. We by and large take the more jobs viewpoint as self-evident truth. Which is understandable – in our world you need a job to earn a living so as to survive. If there is not enough work available for everyone then people suffer.

On the other hand, when I see this world where overproduction seems to be one of our problems – where shops overflow with merchandise, where you can have every little want catered for, where resources are being rapidly depleted and where the environmental results of all this production press for urgent attention, then I can’t help but see an enormous contradiction in being told there is a need to create even more work for us to do.

So why do we need this “more work”?

As I see it there are three main reasons why we work.

The first and most basic of these reasons is to produce the things we need for living. We need food, houses, transport, energy, hospitals, plus a whole host of other things, and work is required to make them possible.

Another reason for working is for personal fulfilment. Whether it is simply to be an active member of the wider community or whether someone is drawn to a particular vocation, most people have a need for some form of activity to occupy their lives with.

The third reason for working is we work to earn a living. Working to earn a living is a crucial part of our economic system. It ensures we all do a fair share of the labour required to produce the stuff we need for living. We need money to gain access to the things necessary for survival and mostly we get that money from a paid job. This inturn ensures that everyone contributes to the general wealth – and it goes on. I know it seems like I am just stating the bleeding obvious here, but I’m attempting to point to something of great import that is usually overlooked in discussions about work and unemployment.

In our world it is essential to have a paid job. When economists and politicians talk about the need to create work it is primarily this third reason for working they are referring to.

In the complex world we live in these three types of work are present in countless variations and combinations. They rarely exist separately. Someone may have a job, a farmer for example; their work not only needs to be done, but also gives them fulfillment and earns them a living – thus combining all three types of work in the one job. As we unfortunately know, there are many jobs that people are only doing to earn a wage but get no satisfaction from and would much rather be somewhere else. And there are those jobs that are not only boring and unpleasant, but would make little difference to our existence if they were not there, except that someone is earning a living from them. More and more in our world the focus is on the third reason for working – working to earn a living.

When looking at these three reasons for working it is important to see that the first two are of a different kind than the third. Working to produce the things we need and working for fulfillment arise directly as a consequence of the physical and mental world we live in. Because we are physical beings we need food and shelter etc and must work to produce them. Because we are psychological/spiritual beings we have a need for a fulfilling life and a need to be part of a wider community.

Working to earn a living on the other hand, is of a different nature. It is a system we have developed to help make our lives more predictable, efficient and fair. Like the rules of the road it only exists because people developed it as a way to deal with a particular situation. Essentially it is a means of fairly distributing the fruits of our combined labour – I do some work, make my contribution to the economy, for which I am given a certain amount of rights, in the form of money, to take what I need from the system. This ensures that everyone does their fair share of the work and no-one abuses the system. Yes it is possible to manipulate things (legally and illegally) so more of the wealth comes my way, but by and large, with a lot of tweaking, the system has served us well. Until now that is.

Something in the working to earn a living system has changed to such an extent that no amount of tweaking is able to keep it operating effectively. In fact trying to keep the system operating as it always has, is resulting in many destructive side effects, such as; overproduction, the marginalised unemployed and soul destroying work lives of large sections of the workforce. It is also preventing a potential worldwide economic utopia from occurring in our lifetimes. No doubt there are many other things that prevent us from having a world where everyone has enough for a fulfilling life, but this is one of the least understood and acknowledged reasons.

What has changed and is causing the system to malfunction is our rising productivity.

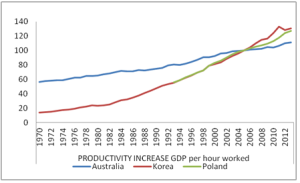

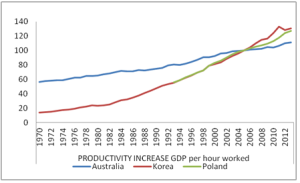

Here are some productivity statistics from the OECD website. Based on GDP per hour worked, Australia’s productivity went from 56.1 in 1970 to 111.3 in 2013. That equates to a doubling of productivity per working person over a period of 43 years. Most industrialised western countries show similar figures to this. For the former eastern European communist countries the increase is even faster. Poland for example went from 55.5 in 1993 to 126.8 in 2013 – more than double the productivity in 20 years. For some of the industrialised Asian countries the figures are astounding. South Korea went from 13.7 in 1970 to 130.3 in 2013 – a tenfold rise in productivity.

While these sorts of figures are not perfect measurements, they do illustrate some significant trends. You could say that in Australia for example we are now able to produce what we did in 1970 with half the labour we needed then. More likely, as working hours have changed little in the last forty years, we are producing around twice as much as we did back then. No wonder it is so difficult to find more jobs for us to do – we are already so overloaded with stuff.

We have just had a guest staying for a few days who brought with her; the latest iphone, an ipod and a laptop – all loaded with 100’s of movies, games, videos and various ways of connecting to the internet. Add to that working, socialising and the practicalities of life, and there really isn’t room to fit in more things. If anything we need more space to properly enjoy the things we already have.

From this perspective, when we look at our economic system’s need for more jobs, it is clear we don’t want the more jobs because we need to produce more stuff. We rather need the jobs to give people access (through wages earned) to things that would have been produced whether they were working in their newly created jobs or not. And politicians and economists talk about even more productivity increases happening – so the problem can only get worse.

A possible solution to this problem can be seen if we look at this growth in productivity from a radically different perspective.

At the moment, each time there is growth in productivity we are left with two choices; there are less hours of work required for the same amount of production and so someone looses their job, or alternatively we produce even more things to give the newly sidelined workers a means to an income. What we rarely consider is; are there better ways to distribute the fruits of our production, to the displaced workers when improved technology or better organisation result in the need for less labour? In that way we would not be continually chasing more jobs – but could fully welcome all of the gifts that increased productivity gives us – then workers would not be seen to be loosing jobs but rather being freed from unnecessary work.

To go down this path of thought is to enter some very dangerous territory. It means a radical rethink of two of the central tenets of our economic system – work and money. As already shown, working to earn a living is a way we have developed to ensure everyone partakes in both the creation and the consumption of the fruits of our labour. It is not a direct outcome of our needs as the other two types of work are, but a system we have created in response to particular circumstances. So if the circumstances change – such as they have with our increased productivity – we are not compelled to continue with a system that can’t seem to deal with the change. We could if we wanted for example, have a 1970 lifestyle and only work 20 hours a week. Or say we still wanted half of the new inventions that have come post 1970, then the work week would be an average of 30 hours – or an extra 10 weeks off per year.

Some economists who argue against these sorts of ideas, put forward what they call “the lump of labour fallacy” or “the luddite fallacy”. They argue that while there may be short term job losses due to new technologies, in the longer term new jobs are always created to take the lost job’s place and so there is no great increase in unemployment. The mechanism whereby this happens is as follows. A new technology makes workers more productive – thus they earn higher wages. Those workers use their increased income to buy more things, thus creating work for the ones who were recently displaced by that new technology. The argument goes that you only have to look at employment levels since the beginning of the industrial revolution to see there has been no outbreak of mass unemployment due to new technology.

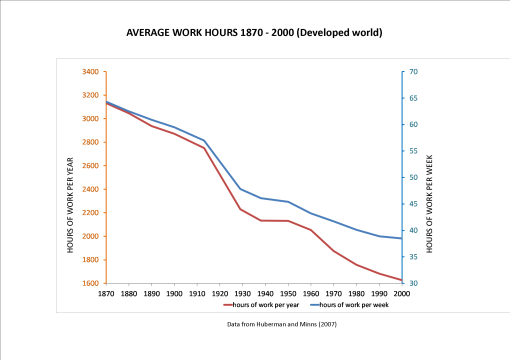

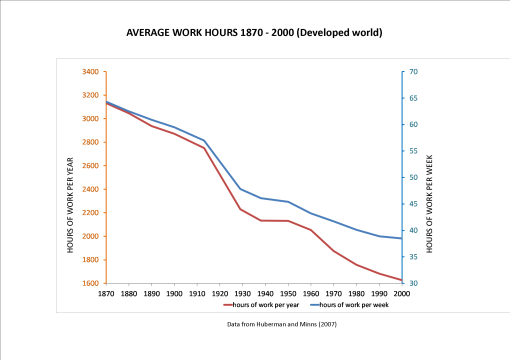

This lump of labour argument conveniently ignores one of the most astounding developments of the industrial revolution. Between 1870 and 1970 the average working week in industrialised countries reduced from around 65 hours to 39 hours (see graph) This is a reduction of 40% off the average working week.

Now by far the majority of these reductions were made possible by labour saving machines. But say if instead of reducing working hours, we would have maintained a 65 hour work week, there would not be enough work for everyone and there would now be a technological unemployment rate of 40%. Technological unemployment and shorter working hours have a direct relationship – they are both outcomes of the same thing.

Now by far the majority of these reductions were made possible by labour saving machines. But say if instead of reducing working hours, we would have maintained a 65 hour work week, there would not be enough work for everyone and there would now be a technological unemployment rate of 40%. Technological unemployment and shorter working hours have a direct relationship – they are both outcomes of the same thing.

The mistake that those who espouse the lump of labour fallacy make is they see unemployment as something bad that needs to be avoided at all costs. Whereas the bulk of the workers who have an extra 25 hours a week to enjoy the fruits of the new technologies know it as a good thing.

Yet in spite of the evidence and commonsense logic, something compels us to persist with our working to earn a living system. – Money. – The general notion is that if someone loses their job because a machine has been invented that will do it faster and better – we have to ‘find the money’ somewhere for them to have a living – which usually means taking it from somewhere else. So often there ends up being less hospitals, or schools, or help for the needy, in order to pay for the results of our increased productivity. As productivity increases we seem to be running faster and faster just to stay in the same spot. I like the solution to this problem proposed by Alan Watts in his essay ‘Wealth Versus Money’. He says that the wealth generated by work done by machines should go to the general community to solve this problem. That something like this doesn’t happen may be one of the reasons why we see more and more of the wealth in our world being held by fewer and fewer people – usually the owners of the technology.

The majority of this essay has been about the ‘working’ part of working to earn a living. The ‘living’ part – usually meaning money – is of a similar nature. Money, like working to earn a living, is a system we have developed over many years to help us deal with the complexities of producing and distributing the fruits of our labour. It does not possess the degree of reality that the goods and services we produce have. In our world though, money has been given a place of equal if not greater importance than the goods and services it represents. For example, look at the global trade in money which largely has as its aim making profits from non-productive money transactions. The amount of money involved in these non-productive transactions is currently hundreds of times greater than the value of trade in real goods and services. So large are these financial markets that a collapse in any of them has the power to bring down the whole world economy (see the recent GFC). So we put enormous amounts of resources into making sure that a handful of investment banks don’t go bankrupt. The derivatives market has grown so large that there is just not enough money in existence to bail out banks if there was a major collapse.

Another example is world hunger. There is currently more than enough food being produced to feed everyone in the world, but because we put such a high priority on making more money, the priority of feeding the hungry is put in second place – or even further down the list.

There is a growing field called Modern Monetary Theory that points out that governments can never be short of their own currency as they are the issuers of it. They have the power to issue themselves as much money as is needed to make use of the productive resources of the country. This could help in the transition to a higher productivity, lower working hour world.

To go into this in more detail is beyond the scope of this essay. Suffice it to say we have the materials and knowledge to produce enough for us all with far less worry and stress than we do at present and one of the reasons we are not doing this is our belief in the need for more work.

![IMG_1815[1]](https://unemploymentisgood.files.wordpress.com/2014/08/img_18151.jpg?w=300&h=184)